Instructional rounds are a powerful tool for school leaders to use in order to improve instruction and student learning. By observing the classroom environment with an appreciative eye, instructional rounds allow school leaders to identify where in the school they can find effective teaching practices and trends that can be replicated across classrooms. Instructional rounds also provide an opportunity for teachers to reflect on their own practice and develop strategies to address areas of improvement. Furthermore, instructional rounds provide a structured way for school leaders to give meaningful feedback to teachers and create a culture of continuous improvement in the school. The collaborative nature of instructional rounds also enables teams of educators to work together and creatively problem-solve issues that may arise in classrooms. By providing an opportunity for all stakeholders to voice their input, instructional rounds are an effective way to build a collaborative and positive learning environment.

From the round which usually takes a day, a number of theories of action are created which link teacher practice and behaviour to student outcomes. Some of the actions are whole school whilst others are teacher strategies. For instance, a school-wide action might read:

“When all the school and all the adults exhibit calm, kind, and respectful language, and nurture positive behaviour, listening carefully to children, then all children respond similarly both to the teacher and to other students, feel safe and secure, and are prepared to engage more in discussions and activities, trusting the adults and feeling valued with a real sense of belonging. “

A teacher strategy might read:

“When adults purposefully develop collaborative and cooperative activities as part of their teaching repertoire, capturing spontaneously learning opportunities, then children build up a range of social skills, can develop a wider range of ideas and solutions and are often able to help one another with their learning and behaviour. “

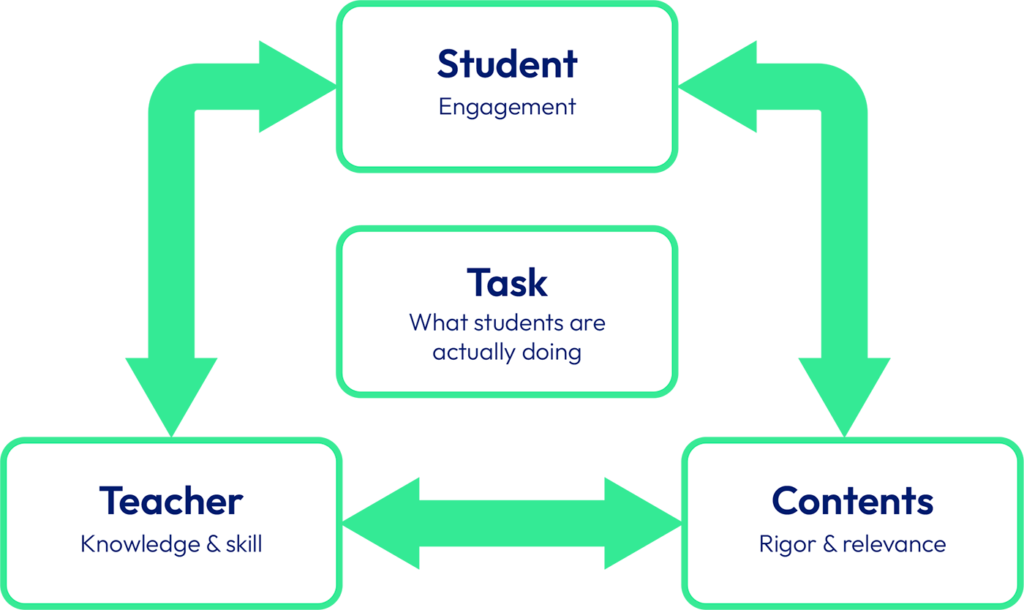

The process can involve 20 to 40 individual observations where we are looking just for those positive actions that are taking place. One can then ask the question, how can we make these successful strategies work in every classroom. It recognises that the answer to school improvement lies within each school and the development of consistent teacher efficacy. The concept is built around the concept of an instructional core.

The Instructional Core

Modified from: City, Elizabeth, et al. Instructional Rounds in Education, 2009

In other words, an appreciative review like this is looking at how all these elements affect what the student is doing, and the effect of that. Changing one element leads to changes in the others so if we are developing a personalised approach and teachers are changing their practice accordingly then student engagement changes and they will have to develop greater regulation and metacognition. The content will need to be re-sequenced, and, in this case, it may demand the development of personal skills.

But the mind-shift is to engage all teachers collaboratively in school improvement from the bottom up.

Having identified those elements of teaching that impact on great learning, schools need to detail what this teaching model involves. You can for instance imagine group work to be a positive collaborative strategy, but it has to be implemented effectively. Ideally the school will work at no more than two or three teacher strategies each year.

A well-researched sequence of implementation would look like this:

- A professional development session that explained the research as to why this model of teaching and learning has impact.

- Demonstration of some of the strategies and techniques. So, for instance if you were developing collaboration in classrooms running a PD session which incorporated a jigsaw activity, or a Socratic Seminar removes any ambiguity and uncertainty and helps them, see how they could use this in their lessons.

- Teachers then need to be able to try it out. Then in groups – and we have seen coaching groups from 2 to 6 people – they support and coach one another, observing one anther where possible, or filming their practice and sharing this with one another.

- It is by taking this time, that we embed practice, just as we do with students when we want to take their learning into the long-term memory. But there should be more. We should ask them to present their learning and the impact to the rest of the faculty. We should encourage action research, hence building up their professional approach to the work.

These rubrics and models of great practice are best developed with all the staff, so they own and understand the skill growth. We do not need to reinvent the wheel, there are lots of resources that can be drawn upon e.g. the work of Tom Sherrington and Oliver Caviglioli and John Saphier.

All of this enables the school to draw up a clear teaching and learning framework that matches the mission and moral purpose of the school. Building rubrics for each theory of action enables teachers to see how they can develop their own practice.

These rubrics and models of great practice are best developed with all the staff, so they own and understand the skill growth. We do not need to reinvent the wheel, there are lots of resources that can be drawn upon e.g. the work of Tom Sherrington and Oliver Caviglioli and John Saphier.

All of this enables the school to draw up a clear teaching and learning framework that matches the mission and moral purpose of the school. Building rubrics for each theory of action enables teachers to see how they can develop their own practice.

Rubrics: High Order Questioning

| Aspiring | Developing | Embedded |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|